Last Wednesday, during our group discussion we wrapped up talking about Laura Mulvey’s article, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In this oddly entertaining piece (let’s face it Freud and feminism always make a great combination), Mulvey argues that women in cinema serve only as scopophilic entities, objects from which men gain sexual stimulation through sight. Aside from this, the cinematic women, Mulvey claims, “[have] not the slightest importance” (203). Our T.A., Jim, asked us at the end of the discussion what our final thoughts were on this Freudian-feminist author, to which I responded, She’s nuts as hell. Care to qualify that? Jim responded lightheartedly. I laughed: at the time, I couldn’t.

And I still can’t. It was true; at the time I thought she was crazy. Women don’t just represent male desires. What about Angelina Jolie in Wanted (2008, Timur Bekmambetov), Uma Thurman in Kill Bill (2003, Quentin Tarantino), or Natalie Portman in V for Vendetta (2005, James McTeigue)? Each is sexy, smart, independent, and kicks ass! They are attractive, yes, but they are also strong-willed and capable. I thought Mulvey must have been at least a little bit full of it.

Then it hit me: times have

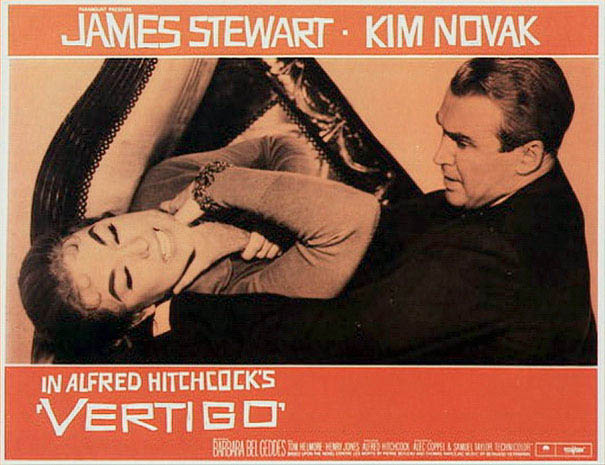

changed… a lot. The films Mulvey discussed were Alfred Hitchcock classics such as Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). Looking at these, Mulvey is completely justified in her views.

Each of the films opens with the leading male in some state of physical emasculation. In Rear Window, we meet Jeffries (James Stewart) in a full lower-body cast, unable to walk or perform his previously adventurous job as a photographer. His accident has left him feeling powerless and dependent on his nurse caretaker, Stella (Thelma Ritter). Similarly, we find Scottie (also James Stewart) in a back brace, suffering from vertigo, unable to continue his job as a policeman—a job which traditionally represents power and strength. In both cases, the leading man is not feeling his manliest. But never fear: this is where the women come in.

Each of James Stewart’s characters has a female counterpart. In Rear Window, his partner in crime is the lovely Lisa Freemont (Grace Kelly). Jeffries, confined to his chair, has been driven to watch out his rear window, following the lives of his neighbors for entertainment. Lisa is his “love interest”, though this term is used very loosely in the film’s opening. Jefferies initially shows very little response to Lisa’s sexual advances, and instead focuses on the lives he is watching. The point at which Jeffries finally begins to pay attention to her is when she becomes involved in his scheme to investigate his potentially murderous neighbor. This increase in his interest coincides with Lisa’s transition from the traditional “passive role” (as Mulvey calls it) that women play to a more active one. However, her actions are not depicted as her own. She is not a free-acting female out to corner crime single-handedly. On the contrary, Hitchcock films the investigation scenes in such a way that it appears that Lisa is just a puppet for Jeffries. She is following his every wish and whim, as Jeffries watches her through binoculars, and as such, becomes not a person, but rather a tool through which Jeffries can regain his masculinity.

In Vertigo the use of women as tools for men is even more apparent. After watching his love interest, Madeline Ester (Kim Novak) hurl herself off of a church steeple, Scottie becomes transfixed on Judy Barton (Kim Novak), a woman who looks mysteriously like the suicidal blonde. Judy becomes so much of a moldable tool for Scottie’s pleasure that she actually allows him to dress her, change her hair and even her mannerisms in order to better suite his desires. Scottie does this in order to be able to recreate the circumstances under which Madeline died, but this time, overcome his acrophobia and save the girl he has built in his love’s image, thus saving and preserving his lost masculinity. In this case, Judy plays no greater role than to fulfill Scottie’s fantasy as the “perfect image of female beauty and mystery” (207).

In each of these films, the main women characters contribute little to the movie in terms of independence and ability to move the plot forward by their own will. Instead, they allow the leading men to realize their full, masculine abilities, while looking exceptionally good (which, let’s be honest, is apparently pretty important to Hitchcock). So while I really wanted to continue on thinking that Laura Mulvey was way off in claiming that women in cinema are only present for male entertainment, I have to say that she is right, at least with respect to the films of her time.

But what about today? Are the beautiful women on screens really here just for the sexual male gaze, or have we as a society progressed to a point where women can be both beautiful and meaningful? Let me know what you think.

This is exactly what I had been thinking about but didn’t know how to express it and you did a great job! I think Mulvey’s article to us now seems ludicrous but her article was written about the films in the early twentieth century when her claims made sense. The female figures in Rear Window and Vertigo were beautiful and powerful so much so that they were put on the backend because the male protagonist had some disability that would intimidate him from treating the female as an equal. Since the film was through the male gaze, he would either ignore the female figures (as in Rear Window) or completely “fetish-ize” the female (Vertigo), but in both films the male figure attempts to control the females as you say like a tool through which the men can gain back their masculinity. Nowadays, I would hope to believe the females in the movies represent their own independency and strength and that the films today have moved away from the traditional, stereotypical view of the women of the early twentieth century.

ReplyDeleteTucker, great post. I was actually thinking of Angelina Jolie when I was commenting on Lyndsay's blog. I argued that in more recent movies, females can be the main character, but then I questioned whether or not male audience members actually identify with them or if the female chracters simply serve as objects of viewing pleasure. I was specifically thinking of Angelina Jolie when I made that post.

ReplyDeleteI really like how in your blog, you discuss how times have changed. I definitely agree with you that Mulvey's writing applied to Hitchcock's times and films, but today, with so many blockbuster actress (Angelina Jolie, Uma Thurman, Julia Roberts etc, these actresses can definitely serve as the protagonist who ALL audience members can identify with rather than simply an object of viewing pleasure.

Tucker! YES! YES YES YES! This is exactly what I wanted someone to post! It is super true that times have changed. Feminism hasn't really kicked in, and it's still in the process of doing so, I believe. I mean, the top CEOs in the country are predominantly male, so of course, as film reflects our society, we are going to be skewed to the male perspective. They're running the industry! I mean honestly, how many blockbusters star female roles? Not as many as those that star men. How many of IMDB's top 250 are starring male roles? What does that say about us? It shows that we are obviously slanted and corrupted in our views. This is the same question that we always ask. To what part of society are we skewed? Well obviously to the most powerful part: the wealthy Caucasian population. That's why so many of the top 250 films of imdb are by white males starring white males. It's cool to see how the scores break down, cause you'll see that something like the Dark Knight is ranked higher by males. Interesting. Good stuff dude.

ReplyDeleteI definitely agree with the overall, substantive argument of your post - that times have changed, film has changed accordingly, and so we do need to take articles by authors such as Mulvey with an eye to context. You bring a sense of common sense into the debate that lends you a great deal of credibility. In fact, it is your ability to take a step back from the purely visceral or emotional first reaction, and to craft your analysis WHILE taking external factors into consideration, that makes your posts so enjoyable and enlightening to read.

ReplyDeleteHaving said that, though, I do have to say I disagree with two minor points of your argument - on the roles of Lisa Freemont and Judy Barton.

As far as Lisa's character goes, I felt that she was actually quite more daring and adventurous than L. B. Jeffries had expected or intended her to be. In fact, one of the primary arguments he had for his opposition to their relationship was that she was the sort of female who could never "get her hands dirty." Therefore, I don't think she was precisely following his wishes in climbing into Thorwald's apartment (as evidenced by his frantic calls for her not to go when he realized her intention). Maybe she was following his wishes on a subconscious level? In the matter of the magazine, however, I think that was a pretty mischievous show of NON-compliance. She'd become the woman he wanted her to be... or so he thinks and she is content to let him think.

As for Judy Barton, I'm definitely not going to try to argue that she was anything but an object of manipulation by men. However, I don't think that Scottie was the one to truly shape, mould, and re-create her character. If anything, I think that Mr. Elster (who we haven't discussed much at all due to the prominence of Judy and Scottie as the main characters, but who undeniably had a huge part to play in bringing about the action in the film) was the one who was, perhaps not as noticeably, the overbearing male character in the film. Consider how well he planned everything how, how well he USED everyone, including Scottie and Judy, and how easily he manipulated his wife for his own ends. He's the hidden villain in all of this, truly.

I think you pose a great point of discussion as to how much things have changed. And I feel that, like so many issues, even though we've come so far, strong female roles are still hard to come by. It's almost amazing when a really unique female role comes along, but you see it happen with males all the time. There are perhaps examples of females breaking barriers, but they aren't consistent. What the problem is and how to fix it, I don't know. Short of Kathryn Bigelow, who did point break and the hurt locker, I can't think of female directors who successfully break barriers (there was an attempt to with jennifer's body, and i must say, it failed horrible). Obviously, the main issue is the male-controlled industry, but I don't know what will stop it and cause distinct (and successful) female visions in film to emerge.

ReplyDeleteTucker,

ReplyDeleteGreat post. I agree that Jeffries certainly uses Lisa to regain his masculinity. He is castrated at the beginning quite literally because he is unable to use anything below the waist (Freud would have loved that). I would say that the women in the Hitchcock movies are meaningful in that they do progress the plot someways (Lisa brings about a confrontation with Thorwald by breaking into his apartment) but overall they are more objects of beauty.

In response to your question I think that women can be both beautiful and meaningful in movies today. But that misses the point. What would be more of a progression would be to have women that are ugly and important. Rather a complete reversal of the women from these movies Rear Window and Vertigo who are beautiful statues.

It's great to read through your intellectual process here and hear you come around to making sense of Mulvey's critique of the male gaze. Her essay also puts forward a solution: cinema without pleasure. That is, if voyeuristic pleasure in the cinema is patterned after male desire, then for Mulvey the solution wasn't stronger female leads, or active female characters. It was much more radical. I think for Mulvey the looking relations of cinema are much deeper than representational concerns (what women are doing on screen). You'd have to see if those movies still promote voyeuristic pleasure in looking-at the female figure (regardless of her narrative function) in order to come to any conclusions about whether cinema is any different. That, or see one of Mulvey's movies (or Yvonne Rainer, or Chantal Ackerman) to see how gazing pleasure is resisted.

ReplyDeleteThe post is hilarious, really. And I enjoyed reading it. You've seen a sequence of Mulvey's own Riddles of the Sphinx, so you know what " cinema wihtout pleasure" might look like v. "badass women" who still command our visual pleasure. Of a different sort.

ReplyDeleteI am glad you wrote on this topic-- somebody had to! I know that I have given a lot of thought to this, and I agree with you entirely. I found myself extremely annoyed while reading Mulvey, because at the time, I found it to be stretching things way too far in the name of feminism. But then I realized: she was writing in a different time, and looking at some of the movies we have viewed from earlier days, I would have been offended/struck by the pattern too. I recognize now that I was just reading from an entirely different perspective-- its amazing how much changes over a few decades. Your examples contrasting past and present are great. Good work :)

ReplyDelete